- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Strategies to strengthen the resilience of primary health care in the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review

BMC Health Services Research volume 24, Article number: 841 (2024)

Abstract

Background

Primary Health Care (PHC) systems are pivotal in delivering essential health services during crises, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. With varied global strategies to reinforce PHC systems, this scoping review consolidates these efforts, identifying and categorizing key resilience-building strategies.

Methods

Adopting Arksey and O'Malley's scoping review framework, this study synthesized literature across five databases and Google Scholar, encompassing studies up to December 31st, 2022. We focused on English and Persian studies that addressed interventions to strengthen PHC amidst COVID-19. Data were analyzed through thematic framework analysis employing MAXQDA 10 software.

Results

Our review encapsulated 167 studies from 48 countries, revealing 194 interventions to strengthen PHC resilience, categorized into governance and leadership, financing, workforce, infrastructures, information systems, and service delivery. Notable strategies included telemedicine, workforce training, psychological support, and enhanced health information systems. The diversity of the interventions reflects a robust global response, emphasizing the adaptability of strategies across different health systems.

Conclusions

The study underscored the need for well-resourced, managed, and adaptable PHC systems, capable of maintaining continuity in health services during emergencies. The identified interventions suggested a roadmap for integrating resilience into PHC, essential for global health security. This collective knowledge offered a strategic framework to enhance PHC systems' readiness for future health challenges, contributing to the overall sustainability and effectiveness of global health systems.

Background

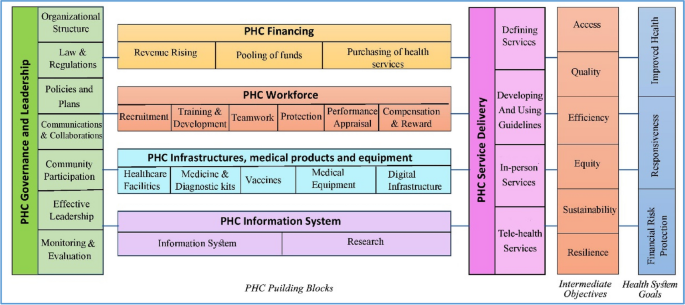

The health system is a complex network that encompasses individuals, groups, and organizations engaged in policymaking, financing, resource generation, and service provision. These efforts collectively aim to safeguard and enhance people health, meet their expectations, and provide financial protection [1]. The World Health Organization's (WHO) framework outlines six foundational building blocks for a robust health system: governance and leadership, financing, workforce, infrastructure along with technologies and medicine, information systems, and service delivery. Strengthening these elements is essential for health systems to realize their objectives of advancing and preserving public health [2].

Effective governance in health systems encompasses the organization of structures, processes, and authority, ensuring resource stewardship and aligning stakeholders’ behaviors with health goals [3]. Financial mechanisms are designed to provide health services without imposing financial hardship, achieved through strategic fund collection, management and allocation [4, 5]. An equitable, competent, and well-distributed health workforce is crucial in delivering healthcare services and fulfilling health system objectives [2]. Access to vital medical supplies, technologies, and medicines is a cornerstone of effective health services, while health information systems play a pivotal role in generating, processing, and utilizing health data, informing policy decisions [2, 5]. Collectively, these components interact to offer quality health services that are safe, effective, timely, affordable, and patient-centered [2]

The WHO, at the 1978 Alma-Ata conference, introduced primary health care (PHC) as the fundamental strategy to attain global health equity [6]. Subsequent declarations, such as the one in Astana in 2018, have reaffirmed the pivotal role of PHC in delivering high-quality health care for all [7]. PHC represents the first level of contact within the health system, offering comprehensive, accessible, community-based care that is culturally sensitive and supported by appropriate technology [8]. Essential care through PHC encompasses health education, proper nutrition, access to clean water and sanitation, maternal and child healthcare, immunizations, treatment of common diseases, and the provision of essential drugs [6]. PHC aims to provide protective, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative services that are as close to the community as possible [9].

Global health systems, however, have faced significant disruptions from various shocks and crises [10], with the COVID-19 pandemic being a recent and profound example. The pandemic has stressed health systems worldwide, infecting over 775 million and claiming more than 7.04 million lives as of April 13th, 2024 [11]. Despite the pandemic highlighting the critical role of hospitals and intensive care, it also revealed the limitations of specialized medicine when not complemented by a robust PHC system [12].

The pandemic brought to light the vulnerabilities of PHC systems, noting a significant decrease in the use of primary care for non-emergency conditions. Routine health services, including immunizations, prenatal care, and chronic disease management, were severely impacted [13]. The challenges—quarantine restrictions, fears of infection, staffing and resource shortages, suspended non-emergency services, and financial barriers—reduced essential service utilization [14]. This led to an avoidance of healthcare, further exacerbating health inequalities and emphasizing the need for more resilient PHC systems [15,16,17].

Resilient PHC systems are designed to predict, prevent, prepare, absorb, adapt, and transform when facing crises, ensuring the continuity of routine health services [18]. Investing in the development of such systems can not only enhance crisis response but also foster post-crisis transformation and improvement. This study focuses on identifying global interventions and strategies to cultivate resilient PHC systems, aiding policymakers and managers in making informed decisions in times of crisis.

Methods

In 2023, we conducted a scoping review to collect and synthesize evidence from a broad spectrum of studies addressing the COVID-19 pandemic. A scoping review allows for the assessment of literature's volume, nature, and comprehensiveness, and is uniquely inclusive of both peer-reviewed articles and gray literature—such as reports, white papers, and policy documents. Unlike systematic reviews, it typically does not require a quality assessment of the included literature, making it well-suited for rapidly gathering a wide scope of evidence [19]. Our goal was to uncover the breadth of solutions aimed at bolstering the resilience of the PHC system throughout the COVID-19 crisis. The outcomes of this review are intended to inform the development of a model that ensures the PHC system's ability to continue delivering not just emergency services but also essential care during times of crisis.

We employed Arksey and O'Malley's methodological framework, which consists of six steps: formulating the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting the pertinent studies, extracting data, synthesizing and reporting the findings, and, where applicable, consulting with stakeholders to inform and validate the results [20]. This comprehensive approach is designed to capture a wide range of interventions and strategies, with the ultimate aim of crafting a robust PHC system that can withstand the pressures of a global health emergency

Stage 1: identifying the research question

Our scoping review was guided by the central question: "Which strategies and interventions have been implemented to enhance the resilience of primary healthcare systems in response to the COVID-19 pandemic?" This question aimed to capture a comprehensive array of responses to understand the full scope of resilience-building activities within PHC systems.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

To ensure a thorough review, we conducted systematic searches across multiple databases, specifically targeting literature up to December 31st, 2022. The databases included PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Magiran, and SID. We also leveraged the expansive reach of Google Scholar. Our search strategy incorporated a bilingual approach, utilizing both English and Persian keywords that encompassed "PHC," "resilience," "strategies," and "policies," along with the logical operators AND/OR to refine the search. Additionally, we employed Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms to enhance the precision of our search. The results were meticulously organized and managed using the Endnote X8 citation manager, facilitating the systematic selection and review of pertinent literature.

Stage 3: selecting studies

In the third stage, we meticulously vetted our search results to exclude duplicate entries by comparing bibliographic details such as titles, authors, publication dates, and journal names. This task was performed independently by two of our authors, LE and MA, who rigorously screened titles and abstracts. Discrepancies encountered during this process were brought to the attention of a third author, AMM, for resolution through consensus.

Subsequently, full-text articles were evaluated by four team members—LE, MA, PI, and SHZ—to ascertain their relevance to our research question. The selection hinged on identifying articles that discussed strategies aimed at bolstering the resilience of PHC systems amidst the COVID-19 pandemic Table 1.

We have articulated the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria that guided our selection process in Table 2, ensuring transparency and replicability of our review methodology

Stage 4: charting the data

Data extraction was conducted by a team of six researchers (LE, MA, PI, MA, FE, and SHZ), utilizing a structured data extraction form. For each selected study, we collated details including the article title, the first author’s name, the year of publication, the country where the study was conducted, the employed research methodology, the sample size, the type of document, and the PHC strengthening strategies described.

In pursuit of maintaining rigorous credibility in our study, we adopted a dual-review process. Each article was independently reviewed by pairs of researchers to mitigate bias and ensure a thorough analysis. Discrepancies between reviewers were addressed through discussion to reach consensus. In instances where consensus could not be reached, the matter was escalated to a third, neutral reviewer. Additionally, to guarantee thoroughness, either LE or MA conducted a final review of the complete data extraction for each study.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing and reporting the results

In this stage, authors LE, MZ, and MA worked independently to synthesize the data derived from the selected studies. Differences in interpretation were collaboratively discussed until a consensus was reached, with AMM providing arbitration where required.

We employed a framework thematic analysis, underpinned by the WHO's health system building blocks model, to structure our findings. This model categorizes health system components into six foundational elements: governance and leadership; health financing; health workforce; medical products, vaccines, and technologies; health information systems; and service delivery [2]. Using MAXQDA 10 software, we coded the identified PHC strengthening strategies within these six thematic areas.

Results

Summary of search results and study selection

In total, 4315 articles were found by initial search. After removing 397 duplicates, 3918 titles and abstracts were screened and 3606 irrelevant ones were deleted. Finally, 167 articles of 312 reviewed full texts were included in data synthesis (Fig. 1). Main characteristics of included studies are presented in Appendix 1.

Characteristics of studies

These studies were published in 2020 (18.6%), 2021 (36.5%) and 2022 (44.9%). They were conducted in 48 countries, mostly in the US (39 studies), the UK (16 studies), Canada (11 studies), Iran (10 studies) and Brazil (7 studies) as shown in Fig. 2.

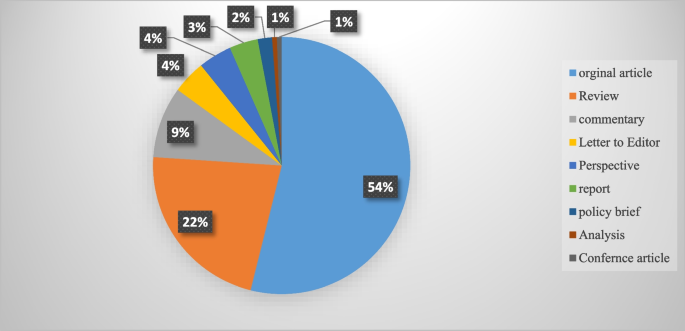

Although the majority of the reviewed publications were original articles (55.1 %) and review papers (21 %), other types of documents such as reports, policy briefs, analysis, etc., were also included in this review (Fig. 3).

Strengthening interventions to build a resilient PHC system

In total, 194 interventions were identified for strengthening the resilience of PHC systems to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. They were grouped into six themes of PHC governance and leadership (46 interventions), PHC financing (21 interventions), PHC workforce (37 interventions), PHC infrastructures, equipment, medicines and vaccines (30 interventions), PHC information system (21 interventions) and PHC service delivery (39 interventions). These strategies are shown in Table 3.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to identify and categorize the range of interventions employed globally to strengthen the resilience of primary healthcare (PHC) systems in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our comprehensive search yielded 194 distinct interventions across 48 countries, affirming the significant international efforts to sustain healthcare services during this unprecedented crisis. These interventions have been classified according to the WHO’s six building block model of health systems, providing a framework for analyzing their breadth and depth. This review complements and expands upon the findings from Pradhan et al., who identified 28 interventions specifically within low and middle-income countries, signaling the universality of the challenge and the myriad of innovative responses it has provoked globally [178].

The review highlights the critical role of governance and leadership in PHC resilience. Effective organizational structure changes, legal reforms, and policy development were crucial in creating adaptive healthcare systems capable of meeting the dynamic challenges posed by the pandemic. These findings resonate with the two strategies of effective leadership and coordination emphasized by Pradhan et al. (2023), and underscore the need for clear vision, evidence-based policy, and active community engagement in governance [178]. The COVID-19 pandemic posed significant challenges for PHC systems globally. A pivotal response to these challenges was the active involvement of key stakeholders in the decision-making process. This inclusivity spanned across the spectrum of general practitioners, health professionals, health managers, and patients. By engaging these vital contributors, it became possible to address their specific needs and to design and implement people-centered services effectively [41,42,43].

The development and implementation of collaborative, evidence-informed policies and national healthcare plans were imperative. Such strategies required robust leadership, bolstered by political commitment, to ensure that the necessary changes could be enacted swiftly and efficiently [41, 45]. Leaders within the health system were called upon to foster an environment of good governance. This entailed promoting increased participation from all sectors of the healthcare community, enhancing transparency in decision-making processes, and upholding the principles of legitimacy, accountability, and responsibility within the health system [10]. The collective aim was to create a more resilient, responsive, and equitable healthcare system in the face of the pandemic's demands.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments were compelled to implement new laws and regulations. These were designed to address a range of issues from professional accreditation and ethical concerns to supporting the families of healthcare workers. Additionally, these legal frameworks facilitated the integration of emerging services such as telemedicine into the healthcare system, ensuring that these services were regulated and standardized [38, 40, 61]. A key aspect of managing the pandemic was the establishment of effective and transparent communication systems for patients, public health authorities, and the healthcare system at large [60, 61]. To disseminate vital information regarding the pandemic, vaccination programs, and healthcare services, authorities leveraged various channels. Public media, local online platforms, and neighborhood networks were instrumental in keeping the public informed about the ongoing situation and available services [53, 60, 86]. For health professionals, digital communication tools such as emails and WhatsApp groups, as well as regular meetings, were utilized to distribute clinical guidelines, government directives, and to address any queries they might have had. This ensured that healthcare workers were kept up-to-date with the evolving landscape of the pandemic and could adapt their practices accordingly [60, 144].

Healthcare facilities function as complex socio-technical entities, combining multiple specialties and adapting to the ever-changing landscape of healthcare needs and environments [179]. To navigate this dynamic, policy makers must take into account an array of determinants—political, economic, social, and environmental—that influence health outcomes. Effective management of a health crisis necessitates robust collaboration across various sectors, including government bodies, public health organizations, primary healthcare systems, and hospitals. Such collaboration is not only pivotal during crisis management but also during the development of preparedness plans [63]. Within the health system, horizontal collaboration among departments and vertical collaboration between the Ministry of Health and other governmental departments are vital. These cooperative efforts are key to reinforce the resilience of the primary healthcare system. Moreover, a strong alliance between national pandemic response teams and primary healthcare authorities is essential to identifying and resolving issues within the PHC system [29]. On an international scale, collaborations and communications are integral to the procurement of essential medical supplies, such as medicines, equipment, and vaccines. These international partnerships are fundamental to ensuring that health systems remain equipped to face health emergencies [63].

To ensure the PHC system's preparedness and response capacity was at its best, regular and effective monitoring and evaluation programs were put in place. These included rigorous quarterly stress tests at the district level, which scrutinized the infrastructure and technology to pinpoint the system’s strengths and areas for improvement [43]. Furthermore, clinical audits were conducted to assess the structure, processes, and outcomes of healthcare programs, thereby enhancing the quality and effectiveness of the services provided [63]. These evaluation measures were crucial for maintaining a high standard of care and for adapting to the ever-evolving challenges faced by the PHC system.

Financial strategies played a critical role in enabling access to essential health services without imposing undue financial hardship. Various revenue-raising, pooling, and purchasing strategies were implemented to expand PHC financing during the pandemic, illustrating the multifaceted approach needed to sustain healthcare operations under strained circumstances [9, 19].

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indian government took decisive action to bolster the country's healthcare infrastructure. By enhancing the financial capacity of states, the government was able to inject more funds into the Primary Health Care (PHC) system. This influx of resources made it possible to introduce schemes providing free medications and diagnostic services [50]. The benefits of increased financial resources were also felt beyond India's borders, enabling the compensation of health services in various forms. In Greece, it facilitated the monitoring and treatment of COVID-19 through in-person, home-based, and remote health services provided by physicians in private practice. Similarly, in Iran, the financial boost supported the acquisition of basic and para-clinical services from the private sector [21, 65]. These measures reflect a broader international effort to adapt and sustain health services during a global health crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a formidable challenge to the PHC workforce worldwide. Healthcare workers were subjected to overwhelming workloads and faced significant threats to both their physical and mental well-being. To build resilience in the face of this crisis, a suite of interventions was implemented. These included recruitment strategies, training and development programs, enhanced teamwork, improved protective measures, comprehensive performance appraisals, and appropriate compensation mechanisms, as documented in Table 3. To address staffing needs within PHC centers, a range of professionals including general practitioners, nurses, community health workers, and technical staff were either newly employed or redeployed from other healthcare facilities [63]. Expert practitioners were positioned on the frontlines, providing both in-person services and telephone consultations, acting as gatekeepers in the health system [49, 63]. Support staff with technological expertise played a crucial role as well, assisting patients in navigating patient portals, utilizing new digital services, and conducting video visits [102]. Furthermore, the acute shortage of healthcare workers was mitigated by recruiting individuals who were retired, not currently practicing, or in training as students, as well as by enlisting volunteers. This strategy was key to bolstering the workforce and ensuring continuity of care during the pandemic [109].

During the pandemic, new training programs were developed to prepare healthcare staff for the evolving demands of their roles. These comprehensive courses covered a wide array of critical topics, including the correct use of personal protective equipment (PPE), the operation of ventilators, patient safety protocols, infection prevention, teamwork, problem-solving, self-care techniques, mental health support, strategies for managing stress, navigating and applying reliable web-based information, emergency response tactics, telemedicine, and direct care for COVID-19 patients [74, 95, 100, 108, 110, 112, 117].

Acknowledging the psychological and professional pressures faced by the primary healthcare workforce, health managers took active measures to safeguard both the physical and mental well-being of their employees during this challenging period [124]. Efforts to protect physical health included monitoring health status, ensuring vaccination against COVID-19, and providing adequate PPE [63, 72]. To address mental health, a variety of interventions were deployed to mitigate anxiety and related issues among frontline workers. In Egypt, for instance, healthcare workers benefited from psychotherapy services and adaptable work schedules to alleviate stress [126]. Singapore employed complementary strategies, such as yoga, meditation, and the encouragement of religious practices, to promote relaxation among staff [133]. In the United States, the Wellness Hub application was utilized as a tool for employees to enhance their mental health [132]. In addition to health and wellness initiatives, there were financial incentives aimed at motivating employees. Payment protocols were revised, and new incentives, including scholarship opportunities and career development programs, were introduced to foster job satisfaction and motivation among healthcare workers [63].

The resilience of PHC systems during the pandemic hinged on several key improvements. Enhancing health facilities, supplying medicines and diagnostic kits, distributing vaccines, providing medical equipment, and building robust digital infrastructure were all fundamental elements that contributed to the strength of PHC systems, as outlined in Table 3. Safe and accessible primary healthcare was facilitated through various means. Wheelchair routes were created for patients to ensure their mobility within healthcare facilities. , dedicated COVID-19 clinics were established, mass vaccination centers were opened to expedite immunization, and mobile screening stations were launched to extend testing capabilities [23, 33, 63, 140].

In Iran, the distribution and availability of basic medicines were managed in collaboration with the Food and Drug Organization, ensuring that essential medications reached those in need [89]. During the outbreak, personal protective equipment (PPE) was among the most critical supplies. Access to PPE was prioritized, particularly for vulnerable groups and healthcare workers, to provide a layer of safety against the virus [63]. Vaccines were made available at no cost, with governments taking active measures to monitor their safety and side effects, to enhance their quality, and to secure international approvals. Furthermore, effective communication strategies were employed to keep the public informed about vaccine-related developments [32, 83].

These comprehensive efforts underscored the commitment to maintaining a resilient PHC system in the face of a global health every individual in the community could access healthcare services. To facilitate this, free high-speed Wi-Fi hotspots were established, enabling patients to engage in video consultations and utilize a range of e-services without the barrier of internet costs crisis. Significant enhancements were made to the digital infrastructure. This expansion was critical in ensuring that [30, 54]. Complementing these measures, a variety of digital health tools were deployed to further modernize care delivery. Countries like Nigeria and Germany, for instance, saw the introduction of portable electrocardiograms and telemedical stethoscopes. These innovations allowed for more comprehensive remote assessments and diagnostics, helping to bridge the gap between traditional in-person consultations and the emerging needs for telemedicine [141, 180].

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, targeted interventions were implemented to bolster information systems and research efforts, as outlined in Table 3. Key among these was the advancement of a modern, secure public health information system to ensure access to health data was not only reliable and timely but also transparent and accurate [33, 45, 49]. The "Open Notes" initiative in the United States exemplified this effort, guaranteeing patient access to, and editorial control over, their health records [141]. Management strategies also promoted the "one-health" approach, facilitating the exchange of health data across various departments and sectors to enhance public health outcomes [10].

In addition to these information system upgrades, active patient surveillance and early warning systems were instituted in collaboration with public health agencies. These systems played a pivotal role in detecting outbreaks, providing precise reports on the incidents, characterizing the epidemiology of pathogens, tracking their spread, and evaluating the efficacy of control strategies. They were instrumental in pinpointing areas of concern, informing smart lockdowns, and improving contact tracing methods [33, 63, 72]. The reinforcement of these surveillance and warning systems had a profound impact on shaping and implementing a responsive strategy to the health crisis [10].

To further reinforce the response to the pandemic, enhancing primary healthcare (PHC) research capacity became crucial. This enabled healthcare professionals and policymakers to discern both facilitators and barriers within the system and to devise fitting strategies to address emerging challenges. To this end, formal advisory groups and multidisciplinary expert panels, which included specialists from epidemiology, clinical services, social care, sociology, policy-making, and management, were convened. These groups harnessed the best available evidence to inform decision-making processes [30]. Consequently, research units were established to carry out regular telephone surveys and to collect data on effective practices, as well as new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches [31, 89]. The valuable insights gained from these research endeavors were then disseminated through trusted channels to both the public and policymakers, ensuring informed decisions at all levels [36].

The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a catalyst for the swift integration of telemedicine into healthcare systems globally. This period saw healthcare providers leverage telecommunication technologies to offer an array of remote services, addressing medical needs such as consultations, diagnosis, monitoring, and prescriptions. This transition was instrumental in ensuring care continuity and mitigating infection risks for both patients and healthcare workers, highlighting an innovative evolution in healthcare delivery [170, 181].

Countries adapted to this new model of healthcare with varied applications: Armenia established telephone follow-ups and video consultations for remote patient care, while e-pharmacies and mobile health tools provided immediate access to medical information and services [29]. In France and the United States, tele-mental health services and online group support became a means to support healthy living during the pandemic [147, 158] . New Zealand introduced the Aroha chatbot, an initiative to assist with mental health management [139].

The implementation and effectiveness of these telehealth services were not limited by economic barriers, as underscored by Pradhan et al. (2023), who noted the key role of telemedicine in low and middle-income countries. These countries embraced the technology to maintain health service operations, proving its global applicability and utility [178]. The widespread adoption of telemedicine, therefore, represents a significant and perhaps lasting shift in healthcare practice, one that has redefined patient care in the face of a global health crisis and may continue to shape the future of healthcare delivery [170, 178, 181].

Conclusion

The study highlighted PHC strengthening strategies in COVID-19 time . Notably, the adaptations and reforms spanned across governance, financing, workforce management, information system, infrastructural readiness, and service delivery enhancements. These interventions collectively contributed to the robustness of health systems against the sudden surge in demand and the multifaceted challenges imposed by the pandemic and resulted.

Significantly, the findings have broader implications for health policy and system design worldwide. The pandemic has highlighted the critical need for resilient health systems that are capable of not only responding to health emergencies but also maintaining continuity in essential services. The strategies documented in this review serve as a template for countries to fortify their health systems by embedding resilience into their PHC frameworks (Fig. 4). Future health crises can be better managed by learning from these evidenced responses, which emphasize the necessity of integrated, well-supported, and dynamically adaptable health care structures.

Looking ahead, realist reviews could play a pivotal role in refining PHC resilience strategies. By understanding the context in which specific interventions succeed or fail, realist reviews can help policymakers and practitioners design more effective health system reforms, as echoed in the need for evidence-based planning in health system governance [9] . These reviews offer a methodological advantage by focusing on the causality between interventions and outcomes, aligning with the importance of effective health system leadership and management [50, 182] . They take into account the underlying mechanisms and contextual factors, thus providing a nuanced understanding that is crucial for tailoring interventions to meet local needs effectively [28, 86] , ultimately leading to more sustainable health systems globally. This shift towards a more analytical and context-sensitive approach in evaluating health interventions, as supported by WHO's framework for action [2, 10] , will be crucial for developing strategies that are not only effective in theory but also practical and sustainable in diverse real-world settings.

Limitations and future research

In our comprehensive scoping review, we analyzed 167 articles out of a dataset of 4,315, classifying 194 interventions that build resilience in primary healthcare systems across the globe in response to pandemics like COVID-19. While the review's extensive search provides a sweeping overview of various strategies, it may not capture the full diversity of interventions across all regions and economies. Future research should focus on meta-analyses to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions in greater detail and employ qualitative studies to delve into the specific challenges and successes, thus gaining a more nuanced understanding of the context. As the review includes articles only up to December 31, 2022, it may overlook more recent studies. Regular updates, a broader linguistic range, and the inclusion of a more diverse array of databases are recommended to maintain relevance and expand the breadth of literature, ultimately guiding more focused research that could significantly enhance the resilience of PHC systems worldwide.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PHC:

-

Primary Health Care

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- UHC:

-

Universal Health Coverage

- PPE:

-

Personal Protective Equipment

- GP:

-

General Practitioner

References

Mosadeghrad AM. A practical model for health policy making and analysis. Payesh. 2022;21(1):7–24 ([in Persian]).

World Health Organization. Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes. WHO’s Framework for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

Khosravi MF, Mosadeghrad AM, Arab M. Health System Governance Evaluation: A Scoping Review. Iran J Public Health. 2023;52(2):265.

Mosadeghrad AM, Abbasi M, Abbasi M, Heidari M. Sustainable health financing methods in developing countries: a scoping review. J of School Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2023;20(4):358–78 ([in Persian]).

Mosadeghrad AM. Health strengthening plan, a supplement to Iran health transformation plan: letter to the editor. Tehran Univ Med J. 2019;77(8):537–8 ([in Persian]).

World Health Organization. Declaration of alma-ata. Copenhagen: Regional Office for Europe; 1978. p. 1–4.

Rasanathan K, Evans TG. Primary health care, the Declaration of Astana and COVID-19. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(11):801.

World Health Organization, UNICEF. Operational framework for primary health care: transforming vision into action. Geneva: World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund; 2020.

Mosadeghrad AM, Heydari M, Esfahani P. Primary health care strengthening strategies in Iran: a realistic review. J School Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2022;19(3):237–58 ([in Persian]).

Sagan A, Webb E, Azzopardi-Muscat N, de la Mata I, McKee M, Figueras J. Health systems resilience during COVID-19: Lessons for building back better. Regional Office for Europe: World Health Organization; 2021.

World Health Organization, Coronavirus (COVID-19) map. Available at https://covid19.who.int//. Access date 14/04/2024.

Plagg B, Piccoliori G, Oschmann J, Engl A, Eisendle K. Primary health care and hospital management during COVID-19: lessons from lombardy. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021:3987–92.

World Health Organization. Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim report, 27 August 2020. World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1.

Mosadeghrad AM, Jajarmizadeh A. Continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tehran Univ Med J. 2021;79(10):831–2 ([in Persian]).

Splinter MJ, Velek P, Ikram MK, Kieboom BC, Peeters RP, Bindels PJ, Ikram MA, Wolters FJ, Leening MJ, de Schepper EI, Licher S. Prevalence and determinants of healthcare avoidance during the COVID-19 pandemic: A population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2021;18(11):e1003854.

Wangmo S, Sarkar S, Islam T, Rahman MH, Landry M. Maintaining essential health services during the pandemic in Bangladesh: the role of primary health care supported by routine health information system. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2021;10(3):93.

Kumpunen S, Webb E, Permanand G, Zheleznyakov E, Edwards N, van Ginneken E, Jakab M. Transformations in the landscape of primary health care during COVID-19: Themes from the European region. Health Policy. 2022;126(5):391–7.

Ezzati F, Mosadeghrad AM, Jaafaripooyan E. Resiliency of the Iranian healthcare facilities against the Covid-19 pandemic: challenges and solutions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(207):1–16.

Mosadeghrad AM, Isfahani P, Eslambolchi L, Zahmatkesh M, Afshari M. Strategies to strengthen a climate-resilient health system: a scoping review. Global Health. 2023;19(1):62.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Social Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Akrami F, Riazi-Isfahani S, Mahdavi hezaveh A, Ghanbari Motlagh A, Najmi M, Afkar M, et al. Iran’s Status of NCDs Prevention and Management Services during COVID-19 Pandemic at PHC Level. SJKU. 2021;26(5):50–68.

Etienne CF, Fitzgerald J, Almeida G, Birmingham ME, Brana M, Bascolo E, Cid C, Pescetto C. COVID-19: transformative actions for more equitable, resilient, sustainable societies and health systems in the Americas. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(8):e003509.

Tabrizi JS, Raeisi A, Namaki S. Primary health care and COVID-19 Pandemic in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Depict Health. 2022;13(Suppl 1):S1-10.

Danhieux K, Buffel V, Pairon A, Benkheil A, Remmen R, Wouters E, Van Olmen J. The impact of COVID-19 on chronic care according to providers: a qualitative study among primary care practices in Belgium. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21:1–6.

Goodyear-Smith F, Kidd M, Oseni TIA, Nashat N, Mash R, Akman M, Phillips RL, van Weel C. Internationalexamples of primary care COVID-19 preparedness and response: a comparison of four countries. Fam MedCommunity Health. 2022;10(2):e001608.

Kinder K, Bazemore A, Taylor M, Mannie C, Strydom S, George J, Goodyear-Smith F. Integrating primary care and public health to enhance response to a pandemic. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2021;22:e27.

De Maeseneer J. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2021;22:e73.

Westfall JM, Liaw W, Griswold K, Stange K, Green LA, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Jaén CR, Hughes LS, DeVoe J, Gullett H. Uniting public health and primary care for healthy communities in the COVID-19 era and beyond. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(Supplement):S203-9.

Johansen AS, Shriwise A, Lopez-Acuna D, Vracko P. Strengthening the primary health care response to COVID-19: an operational tool for policymakers. Prim Health Care ResDev. 2021;22:e81.

Reath J, Lau P, Lo W, Trankle S, Brooks M, Shahab Y, Abbott P. Strengthening learning and research in health equity–opportunities for university departments of primary health care and general practice. Aust J Prim Health. 2022;29(2):131–6.

Ferenčina J, Tomšič V. COVID-19 clinic as a basis of quality primary health care in the light of the pandemic - an observational study. Med Glas (Zenica). 2022;19(1). https://doi.org/10.17392/1437-21.

Mosadeghrad AH. Promote COVID-19 vaccination uptake: a letter to editor. Tehran Univ Med Sci J. 2022;80(2):159–60.

Chaiban L, Benyaich A, Yaacoub S, Rawi H, Truppa C, Bardus M. Access to primary and secondary health care services for people living with diabetes and lower-limb amputation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Lebanon: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):593.

Džakula A, Banadinović M, Lovrenčić IL, Vajagić M, Dimova A, Rohova M, Minev M, Scintee SG, Vladescu C, Farcasanu D, Robinson S. A comparison of health system responses to COVID-19 in Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania in 2020. Health Policy. 2022;126(5):456–64.

Ghazi Saeedi M, Tanhapour M. Telemedicine System: A Mandatory Requirement in Today’s World. Payavard. 2022;15(5):490–507.

Ferorelli D, Nardelli L, Spagnolo L, Corradi S, Silvestre M, Misceo F, Marrone M, Zotti F, Mandarelli G, Solarino B, Dell’Erba A. Medical legal aspects of telemedicine in Italy: application fields, professional liability and focus on care services during the COVID-19 health emergency. J Prim CareCommun Health. 2020;11:2150132720985055.

Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Auerbach J, Fick DM, Galambos C, Johnson KS. Actualizing better health and health care for older adults: commentary describes six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older Americans. Health Aff. 2021;40(2):219–25.

Hernández Rincón EH, Pimentel González JP, Aramendiz Narváez MF, Araujo Tabares RA, Roa González JM. Description and analysis of primary care-based COVID-19 interventions in Colombia. Medwave. 2021;21(3):e8147.

Giannopoulou I, Tsobanoglou GO. COVID-19 pandemic: challenges and opportunities for the Greek health care system. Irish J Psychol Med. 2020;37(3):226–30.

Chow C, Goh SK, Tan CS, Wu HK, Shahdadpuri R. Enhancing frontline workforce volunteerism through exploration of motivations and impact during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021;1(66):102605.

Alboksmaty A, Kumar S, Parekh R, Aylin P. Management and patient safety of complex elderly patients in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK—Qualitative assessment. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248387.

Savoy A, Patel H, Shahid U, Offner AD, Singh H, Giardina TD, Meyer AN. Electronic Co-design (ECO-design) Workshop for Increasing Clinician Participation in the Design of Health Services Interventions: Participatory Design Approach. JMIR Hum Fact. 2022;9(3):e37313.

Tumusiime P, Karamagi H, Titi-Ofei R, Amri M, Seydi AB, Kipruto H, Droti B, Zombre S, Yoti Z, Zawaira F, Cabore J. Building health system resilience in the context of primary health care revitalization for attainment of UHC: proceedings from the Fifth Health Sector Directors’ Policy and Planning Meeting for the WHO African Region. BMC Proc. 2020;14:1–8 (BioMed Central).

Atoofi MK, Rezaei N, Kompani F, Shirzad F, Sh D. Requirements of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2020;26(3):264–79.

Mosadeghrad AM, Taherkhani T, Shojaei S, Jafari M, Mohammadi S, Emamzadeh A, Akhavan S. Strengthening primary health care system resilience in COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. sjsph 2022;20(1):13-24.

Fotokian Z, Mohammadkhah F. Primary health care as a strategy to fight COVID-19 pandemic: letter to the editor. J Isfahan Med School. 2021;39(630):470–4. https://doi.org/10.22122/jims.v39i630.14016.

Li D, Howe AC, Astier-Peña MP. Primary health care response in the management of pandemics: Learnings from the COVID-19 pandemic. Atención Primaria. 2021;1(53):102226.

Chua AQ, Tan MMJ, Verma M, Han EKL, Hsu LY, Cook AR, et al. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(9):e003317.

Eisele M, Pohontsch NJ, Scherer M. Strategies in primary care to face the SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic: an online survey. Front Med. 2021;2(8):613537.

Lamberti-Castronuovo A, Valente M, Barone-Adesi F, Hubloue I, Ragazzoni L. Primary health care disaster preparedness: a review of the literature and the proposal of a new framework. Int J Dis Risk Reduct. 2022;2:103278.

Piché-Renaud PP, Ji C, Farrar DS, Friedman JN, Science M, Kitai I, Burey S, Feldman M, Morris SK. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the provision of routine childhood immunizations in Ontario Canada. Vaccine. 2021;39(31):4373–82.

Saxenian H, Alkenbrack S, Freitas Attaran M, Barcarolo J, Brenzel L, Brooks A, Ekeman E, Griffiths UK, Rozario S, Vande Maele N, Ranson MK. Sustainable financing for Immunization Agenda 2030. Vaccine. 2024;42 Suppl 1:S73-S81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.11.037.

Saso A, Skirrow H, Kampmann B. Impact of COVID-19 on immunization services for maternal and infant vaccines: results of a survey conducted by imprint—the immunising pregnant women and infants network. Vaccines. 2020;8(3):556.

Sagan A, Thomas S, McKee M, Karanikolos M, Azzopardi-Muscat N, de la Mata I, Figueras J, World Health Organization. COVID-19 and health systems resilience: lessons going forwards. Eurohealth. 2020;26(2):20–4.

Celuppi IC, Meirelles BH, Lanzoni GM, Geremia DS, Metelski FK. Management in the care of people with HIV in primary health care in times of the new coronavirus. Revista de Saúde Pública. 2022;1(56):13.

Denis JL, Potvin L, Rochon J, Fournier P, Gauvin L. On redesigning public health in Québec: lessons learned from the pandemic. Can J Public Health= Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique. 2020;111(6):912.

Wilson G, Windner Z, Dowell A, Toop L, Savage R, Hudson B. Navigating the health system during COVID-19: primary care perspectives on delayed patient care. N Z Med J. 2021;134(1546):17–27 (PMID: 34855730).

Zhang N, Yang S, Jia P. Cultivating resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: a socioecological perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2022;4(73):575–98. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-030221-031857. (Epub 2021 Sep 27 PMID: 34579547).

Al Ghafri T, Al Ajmi F, Al Balushi L, Kurup PM, Al Ghamari A, Al Balushi Z, Al Fahdi F, Al Lawati H, Al Hashmi S, Al Manji A, Al Sharji A. Responses to the pandemic covid-19 in primary health care in oman: muscat experience. Oman Med J. 2021;36(1):e216.

Adler L, Vinker S, Heymann AD, Van Poel E, Willems S, Zacay G. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary care physicians in Israel, with comparison to an international cohort: a cross-sectional study. Israel J Health Policy Res. 2022;11(1):1.

Haldane V, Zhang Z, Abbas RF, Dodd W, Lau LL, Kidd MR, Rouleau K, Zou G, Chao Z, Upshur RE, Walley J. National primary care responses to COVID-19: a rapid review of the literature. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e041622.

Hussein ES, Al-Shenqiti AM, Ramadan RM. Applications of medical digital technologies for noncommunicable diseases for follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12682.

Desborough J, Dykgraaf SH, Phillips C, Wright M, Maddox R, Davis S, Kidd M. Lessons for the global primary care response to COVID-19: a rapid review of evidence from past epidemics. Fam Pract. 2021;38(6):811–25.

Sandhu HS, Smith RW, Jarvis T, O’Neill M, Di Ruggiero E, Schwartz R, Rosella LC, Allin S, Pinto AD. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on public health systems and practice in 3 Canadian provinces from the perspective of public health leaders: a qualitative study. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(6):702–11.

Farsalinos K, Poulas K, Kouretas D, Vantarakis A, Leotsinidis M, Kouvelas D, Docea AO, Kostoff R, Gerotziafas, Antoniou MN, Polosa R. Improved strategies to counter the COVID-19 pandemic: Lockdowns vs. primary and community healthcare. Toxicol Rep. 2021;8:1–9.

Fitzpatrick K, Sehgal A, Montesanti S, Pianarosa E, Barnabe C, Heyd A, Kleissen T, Crowshoe L. Examining the role of Indigenous primary healthcare across the globe in supporting populations during public health crises. Global Public Health. 2022;24:1–29.

Liaw ST, Kuziemsky C, Schreiber R, Jonnagaddala J, Liyanage H, Chittalia A, Bahniwal R, He JW, Ryan BL, Lizotte DJ, Kueper JK. Primary care informatics response to Covid-19 pandemic: adaptation, progress, and lessons from four countries with high ICT development. Yearbook Med Inform. 2021;30(01):044–55.

Djalante R, Shaw R, DeWit A. Progress in disaster. Science. 2020;6:100080.

Fatima R, Akhtar N, Yaqoob A, Harries AD, Khan MS. Building better tuberculosis control systems in a post-COVID world: learning from Pakistan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;1(113):S88-90.

Shin WY, Kim C, Lee SY, Lee W, Kim JH. Role of primary care and challenges for public–private cooperation during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: An expert Delphi study in South Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2021;62(7):660.

Thompson RN, et al. Key questions for modelling COVID-19exit strategies. Proc R Soc B. 2020;287:20201405. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.1405.

Baral P. Health systems and services during COVID-19: lessons and evidence from previous crises: a rapid scoping review to inform the United Nations research roadmap for the COVID-19 recovery. Int J Health Serv. 2021;51(4):474–93.

Daou M, Helou S, El Helou J, El Hachem C, El Helou E. Ensuring care continuity in extreme crises: A participatory action research approach. InMEDINFO 2021: One World, One Health–Global Partnership for Digital Innovation 2022 (pp. 937-941). IOS Press.

Besigye IK, Namatovu J, Mulowooza M. Coronavirus disease-2019 epidemic response in Uganda: the need to strengthen and engage primary healthcare. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2020;12(1):1–3.

Silva MJ, Santos P. The impact of health literacy on knowledge and attitudes towards preventive strategies against COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105421. (PMID:34069438;PMCID:PMC8159089).

Sultana A, Bhattacharya S, Hossain MM. COVID-19 and primary care: a critical need for strengthening emergency preparedness across health systems. J Fam Med Primary Care. 2021;10(1):584–5.

Xu RH, Shi LS, Xia Y, Wang D. Associations among eHealth literacy, social support, individual resilience, and emotional status in primary care providers during the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant. Digit Health. 2022;25(8):20552076221089788. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221089789. (PMID:35355807;PMCID:PMC8958311).

Bajgain BB, Jackson J, Aghajafari F, Bolo C, Santana MJ. Immigrant Healthcare Experiences and Impacts During COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study in Alberta Canada. J Patient Exp. 2022;9:23743735221112708.

Kim AY, Choi WS. Considerations on the implementation of the telemedicine system encountered with stakeholders’ resistance in COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed e-Health. 2021;27(5):475–80.

Tayade MC. Strategies to tackle by primary care physicians to mental health issues in India in COVId-19 pandemic. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020;9(11):5814–5.

Thomas C. Resilient health and care: Learning the lessons of Covid-19 in the English NHS, IPPR. 2020. http://www.ippr.org/research/publications/resilient-health-and-care.

Saab MM, O’Driscoll M, FitzGerald S, Sahm LJ, Leahy-Warren P, Noonan B, Kilty C, Lyons N, Burns HE, Kennedy U, Lyng Á. Primary healthcare professionals’ perspectives on patient help-seeking for lung cancer warning signs and symptoms: a qualitative study. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):1–5.

Ma L, Han X, Ma Y, Yang Y, Xu Y, Liu D, Yang W, Feng L. Decreased influenza vaccination coverage among Chinese healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Dis Pov. 2022;11(05):63–73.

Ismail SA, Lam ST, Bell S, Fouad FM, Blanchet K, Borghi J. Strengthening vaccination delivery system resilience in the context of protracted humanitarian crisis: a realist-informed systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1–21.

Litke N, Weis A, Koetsenruijter J, Fehrer V, Koeppen M, Kuemmel S, Szecsenyi J, Wensing M. Building resilience in German primary care practices: a qualitative study. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):1–4.

Den Broeder L, South J, Rothoff A, Bagnall AM, Azarhoosh F, Van Der Linden G, Bharadwa M, Wagemakers A. Community engagement in deprived neighbourhoods during the COVID-19 crisis: perspectives for more resilient and healthier communities. Health promotion international. 2022;37(2):daab098.

Sundararaman T, Muraleedharan VR, Ranjan A. Pandemic resilience and health systems preparedness: lessons from COVID-19 for the twenty-first century. J Soc Econ Dev. 2021;23(Suppl 2):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-020-00133-x. (Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34720480; PMCID: PMC7786882).

Ferreira NN, Garibaldi PM, Moraes GR, Moura JC, Klein TM, Machado LE, Scofoni LF, Haddad SK, Calado RT, Covas DT, Fonseca BA. The impact of an enhanced health surveillance system for COVID-19 management in Serrana, Brazil. Public Health Pract. 2022;1(4):100301.

Harzheim E, Martins C, Wollmann L, Pedebos LA, Faller LD, Marques MD, Minei TS, Cunha CR, Telles LF, Moura LJ, Leal MH. Federal actions to support and strengthen local efforts to combat COVID-19: Primary Health Care (PHC) in the driver’s seat. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2020;5(25):2493–7.

Smaggus A, Long J, Ellis LA, Clay-Williams R, Braithwaite J. Government actions and their relation to resilience in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic in New South Wales, Australia and Ontario, Canada. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(9):1682–94. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2021.67.

Tselebis A, Pachi A. Primary mental health care in a New Era. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(10):2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10102025. (PMID:36292472;PMCID:PMC9601948).

Rieckert A, Schuit E, Bleijenberg N, Ten Cate D, de Lange W, de Man-van Ginkel JM, Mathijssen E, Smit LC, Stalpers D, Schoonhoven L, Veldhuizen JD, Trappenburg JC. How can we build and maintain the resilience of our health care professionals during COVID-19? Recommendations based on a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e043718. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043718.

Basu P, Alhomoud S, Taghavi K, Carvalho AL, Lucas E, Baussano I. Cancer screening in the coronavirus pandemic era: adjusting to a new situation. JCO Global Oncol. 2021;7(1):416–24.

Rieckert A, Schuit E, Bleijenberg N, et al. How can we build and maintain the resilience of our health care professionals during COVID-19? Recommendations based on a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e043718. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043718.

Shaikh BT. Strengthening health system building blocks: configuring post-COVID-19 scenario in Pakistan. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2021;22:e9 Cambridge University Press.

Franzosa E, Gorbenko K, Brody AA, Leff B, Ritchie CS, Kinosian B, Ornstein KA, Federman AD. “At home, with care”: lessons from New York City home-based primary care practices managing COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(2):300–6.

Adhikari B, Mishra SR, Schwarz R. Transforming Nepal’s primary health care delivery system in global health era: addressing historical and current implementation challenges. Global Health. 2022;18(1):1–2.

Mas Bermejo P, Sánchez Valdés L, Somarriba López L, Valdivia Onega NC, Vidal Ledo MJ, Alfonso Sánchez I, et al. Equity and the Cuban National Health System's response to COVID-19. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2021;45:e80. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2021.80.

Gong F, Hu G, Lin H, Sun X, Wang W. Integrated Healthcare Systems Response Strategies Based on the Luohu Model During the COVID-19 Epidemic in Shenzhen, China. Int J Integr Care. 2021;21(1):1. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5628.

Gomez T, Anaya YB, Shih KJ, Tarn DM. A qualitative study of primary care physicians’ experiences with telemedicine during COVID-19. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(Supplement):S61-70.

Teng K, Russo F, Kanuch S, Caron A. Virtual Care Adoption-Challenges and Opportunities From the Lens of Academic Primary Care Practitioners. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(6):599–602. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001548. (Epub 2022 Aug 27. PMID: 36037465; PMCID: PMC9555588).

Anaya YB, Mota AB, Hernandez GD, Osorio A, Hayes-Bautista DE. Post-pandemic telehealth policy for primary care: an equity perspective. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(3):588–92.

Florea M, Lazea C, Gaga R, Sur G, Lotrean L, Puia A, Stanescu AM, Lupsor-Platon M, Florea H, Sur ML. Lights and shadows of the perception of the use of telemedicine by Romanian family doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:1575.

Selick A, Durbin J, Hamdani Y, Rayner J, Lunsky Y. Accessibility of Virtual Primary Care for Adults With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Study. JMIR Form Res 2022;6(8):e38916. https://formative.jmir.org/2022/8/e38916. https://doi.org/10.2196/38916.

Frost R, Nimmons D, Davies N. Using remote interventions in promoting the health of frail older persons following the COVID-19 lockdown: challenges and solutions. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2020;21(7):992.

Suija K, Mard LA, Laidoja R, et al. Experiences and expectation with the use of health data: a qualitative interview study in primary care. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23:159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01764-1.

Sullivan EE, McKinstry D, Adamson J, Hunt L, Phillips RS, Linzer M. Burnout Among Missouri Primary Care Clinicians in 2021: Roadmap for Recovery? Mo Med. 2022;119(4):397–400 (PMID: 36118800; PMCID: PMC9462904).

Tang C, Chen X, Guan C, Fang P. Attitudes and Response Capacities for Public Health Emergencies of Healthcare Workers in Primary Healthcare Institutions: A Cross-Sectional Investigation Conducted in Wuhan, China, in 2020. Int Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12204. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912204.

Haldane V, De Foo C, Abdalla SM, Jung AS, Tan M, Wu S, Chua A, Verma M, Shrestha P, Singh S, Perez T. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):964–80.

Haldane V, De Foo C, Abdalla SM, Jung AS, Tan M, Wu S, Chua A, Verma M, Shrestha P, Singh S, Perez T, Tan SM, Bartos M, Mabuchi S, Bonk M, McNab C, Werner GK, Panjabi R, Nordström A, Legido-Quigley H. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):964-80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01381-y.

Berger Z, De Jesus VA, Assoumou SA, Greenhalgh T. Long COVID and health inequities: the role of primary care. Milbank Q. 2021;99(2):519.

Haldane V, Dodd W, Kipp A, Ferrolino H, Wilson K, Servano D, Lau LL, Wei X. Extending health systems resilience into communities: a qualitative study with community-based actors providing health services during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1–2.

Haun JN, Cotner BA, Melillo C, Panaite V, Messina W, Patel-Teague S, Zilka B. Proactive integrated virtual healthcare resource use in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–4.

Kelly F, Uys M, Bezuidenhout D, Mullane SL, Bristol C. Improving Healthcare Worker Resilience and Well-Being During COVID-19 Using a Self-Directed E-Learning Intervention. Front Psychol. 2021;12:748133. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.748133.

Thekkur P, Fernando M, Nair D, Kumar AMV, Satyanarayana S, Chandraratne N, Chandrasiri A, Attygalle DE, Higashi H, Bandara J, Berger SD, Harries AD. Primary Health Care System Strengthening Project in Sri Lanka: Status and Challenges with Human Resources, Information Systems, Drugs and Laboratory Services. Healthcare. 2022;10(11):2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112251.

Balogun M, Banke-Thomas A, Gwacham-Anisiobi U, Yesufu V, Ubani O, Afolabi BB. Actions and AdaptationsImplemented for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Service Provision During the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Lagos, Nigeria: Qualitative Study of Health Facility Leaders. Ann Glob Health. 2022;88(1):13. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3529.

Llamas S, MP AP, Felipe P. Patient safety training and a safe teaching in primary care. Aten Primaria. 2021;53 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):102199.

Eze-Emiri C, Patrick F, Igwe E, Owhonda G. Retrospective study of COVID-19 outcomes among healthcare workers in Rivers State, Nigeria. BMJ Open. 2022;12(11):e061826.

Golechha M, Bohra T, Patel M, Khetrapal S. Healthcare worker resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study of primary care providers in India. World Med Health Policy. 2022;14(1):6–18.

Gómez-Restrepo C, Cepeda M, Torrey WC, Suarez-Obando F, Uribe-Restrepo JM, Park S, Acosta MP, Camblor PM, Castro SM, Aguilera-Cruz J, González L. Perceived access to general and mental healthcare in primary care in Colombia during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022;10:896318.

Nejat N, Borzabadi Farahani Z. COVID-19 pandemic: opportunities for continuing nursing professional development. J Med Educ Dev. 2022;14(44):1–2.

DeVoe JE, Cheng A, Krist A. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(4):e200423.

Hoeft TJ, Hessler D, Francis D, Gottlieb LM. Applying lessons from behavioral health integration to social care integration in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(4):356–61.

Silsand L, Severinsen GH, Berntsen G. Preservation of Person-Centered care through videoconferencing for patient follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic: case study of a multidisciplinary care team. JMIR Format Res. 2021;5(3):e25220.

Sullivan E, Phillips R.S. Sustaining primary care teams in the midst of a pandemic. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2020; 9. 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-020-00434-w.

Abd El Kader AI, Faramawy MA. COVID-19 anxiety and organizational commitment among front line nurses: Perceived role of nurse managers' caring behavior. Nurs Pract Today. 2022;9(1):X.

Croghan IT, Chesak SS, Adusumalli J, Fischer KM, Beck EW, Patel SR, Ghosh K, Schroeder DR, Bhagra A. Stress, resilience, and coping of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Prim Care Commun Health. 2021;12:21501327211008450.

Aragonès E, del Cura-González I, Hernández-Rivas L, Polentinos-Castro E, Fernández-San-Martín MI, López-Rodríguez JA, Molina-Aragonés JM, Amigo F, Alayo I, Mortier P, Ferrer M. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary care workers: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(720):e501-10.

Franck E, Goossens E, Haegdorens F, Geuens N, Portzky M, Tytens T, Dilles T, Beeckman K, Timmermans O, Slootmans S, Van Rompaey B. Role of resilience in healthcare workers’ distress and somatization during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study across Flanders Belgium. Nurs Open. 2022;9(2):1181–9.

DeTore NR, Sylvia L, Park ER, Burke A, Levison JH, Shannon A, et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;146:228–33.

Shi LS, Xu RH, Xia Y, Chen DX, Wang D. The impact of COVID-19-related work stress on the mental health of primary healthcare workers: the mediating effects of social support and resilience. Front Psychol. 2022;21(12):800183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800183. (PMID:35126252;PMCID:PMC8814425).

Golden EA, Zweig M, Danieletto M, Landell K, Nadkarni G, Bottinger E, Katz L, Somarriba R, Sharma V, Katz CL, Marin DB. A resilience-building app to support the mental health of health care workers in the COVID-19 era: Design process, distribution, and evaluation. JMIR Format Res. 2021;5(5):e26590.

Chan AY, Ting C, Chan LG, Hildon ZJ. “The emotions were like a roller-coaster”: a qualitative analysis of e-diary data on healthcare worker resilience and adaptation during the COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore. Hum Resour Health. 2022;20(1):60.

Ashley C, James S, Williams A, Calma K, Mcinnes S, Mursa R, Stephen C, Halcomb E. The psychological well-being of primary healthcare nurses during COVID-19: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(9):3820–8.

Carmona LE, Nielfa MD, Alvarado AL. The Covid-19 pandemic seen from the frontline. Int Braz J Urol. 2020;27(46):181–94.

Delobelle PA, Abbas M, Datay I, De Sa A, Levitt N, Schouw D, Reid S. Non-communicable disease care and management in two sites of the Cape Town Metro during the first wave of COVID-19: A rapid appraisal. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2022;14(1):e1-e7. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v14i1.3215.

Luciani S, Agurto I, Caixeta R, Hennis A. Prioritizing noncommunicable diseases in the Americas region in the era of COVID-19. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2022;46:e83. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2022.83.

Cabral IE, Pestana-Santos M, Ciuffo LL, Nunes YDR, Lomba MLLF. Child health vulnerabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil and Portugal. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2021;29:e3422. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.4805.3422. (Published 2021 Jul 2).

Ludin N, Holt-Quick C, Hopkins S, Stasiak K, Hetrick S, Warren J, Cargo T. A Chatbot to support young people during the COVID-19 Pandemic in New Zealand: evaluation of the real-world rollout of an open trial. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(11):e38743.

Breton M, Deville-Stoetzel N, Gaboury I, Smithman MA, Kaczorowski J, Lussier MT, Haggerty J, Motulsky A, Nugus P, Layani G, Paré G. Telehealth in primary healthcare: a portrait of its rapid implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare Policy. 2021;17(1):73.

Knop M, Mueller M, Niehaves B. Investigating the use of telemedicine for digitally mediated delegation in team-based primary care: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(8):e28151.

Zamiela C, Hossain NUI, Jaradat R. Enablers of resilience in the healthcare supply chain: A case study of U.S healthcare industry during COVID-19 pandemic. Res Transport Econ. 2022;93:101174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2021.101174. Epub 2021 Dec 24. PMCID: PMC9675944.

Lukong AM, Jafaru Y. Covid-19 pandemic challenges, coping strategies and resilience among healthcare workers: a multiple linear regression analysis. Afr J Health Nurs Midwifery. 2021;4:16–27.

Hearnshaw S, Serban S, Mohammed I, Zubair A, Jaswal D, Grant S. A local dental network approach to the COVID-19 pandemic: innovation through collaboration. Prim Dental J. 2021;10(1):33–9.

Haase CB, Bearman M, Brodersen J, Hoeyer K, Risor T. ‘You should see a doctor’, said the robot: Reflections on a digital diagnostic device in a pandemic age. Scand J Public Health. 2021;49(1):33–6.

Otu A, Okuzu O, Ebenso B, Effa E, Nihalani N, Olayinka A, Yaya S. Introduction of mobilehealth tools to support COVID-19 training and surveillance in Ogun State Nigeria. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities. 2021;3:638278:1-9.

Ibragimov K, Palma M, Keane G, Ousley J, Crowe M, Carreño C, Casas G, Mills C, Llosa A. Shifting to Tele-Mental Health in humanitarian and crisis settings: an evaluation of Médecins Sans Frontières experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Conflict Health. 2022;16(1):1–5.

Wherton J, Greenhalgh T, Hughes G, Shaw SE. The role of information infrastructures in scaling up video consultations during COVID-19: mixed methods case study into opportunity, disruption, and exposure. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(11):e42431. https://doi.org/10.2196/42431. (PMID:36282978;PMCID:PMC9651004).

Jonnagaddala J, Godinho MA, Liaw ST. From telehealth to virtual primary care in Australia? a rapid scoping review. Int J Med Inform. 2021;1(151):104470.

Tanemura N, Chiba T. The usefulness of a checklist approach-based confirmation scheme in identifying unreliable COVID-19-related health information: a case study in Japan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2022;9(1):270. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01293-3. (Epub 2022 Aug 15. PMID: 35990766; PMCID: PMC9376898).

Zaroushani V. Occupational safety and health and response to COVID-19 using the fourth industrial revolution technologies. J Health Saf Work. 2020;10(4):329–48.

Binagwaho A, Hirwe D, Mathewos K. Health System Resilience: Withstanding Shocks and Maintaining Progress. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2022;10(Suppl 1):e2200076. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-22-00076.

Freed SL, Thiele D, Gardner M, Myers E. COVID-19 evaluation and testing strategies in a federally qualified health center. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(S3):S284-7.

Levy P, McGlynn E, Hill AB, Zhang L, Korzeniewski SJ, Foster B, Criswell J, O’Brien C, Dawood K, Baird L, Shanley CJ. From pandemic response to portable population health: a formative evaluation of the Detroit mobile health unit program. Plos One. 2021;16(11):e0256908.

Corwin C, Sinnwell E, Culp K. A mobile primary care clinic mitigates an early COVID-19 outbreak among migrant farmworkers in Iowa. J Agromed. 2021;26(3):346–51.

Mills WR, Buccola JM, Sender S, Lichtefeld J, Romano N, Reynolds K, Price M, Phipps J, White L, Howard S. Home-based primary care led-outbreak mitigation in assisted living facilities in the first 100 days of coronavirus disease 2019. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2020;21(7):951–3.

Sigurdsson EL, Blondal AB, Jonsson JS, Tomasdottir MO, Hrafnkelsson H, Linnet K, Sigurdsson JA. How primary healthcare in Iceland swiftly changed its strategy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e043151. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043151. (PMID:33293329;PMCID:PMC7722808).

Mirsky JB, Thorndike AN. Virtual group visits: hope for improving chronic disease management in primary care during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Health Promot. 2021;35(7):904–7.

Lauriola P, Martín-Olmedo P, Leonardi GS, Bouland C, Verheij R, Dückers ML, Van Tongeren M, Laghi F, Van Den Hazel P, Gokdemir O, Segredo E. On the importance of primary and community healthcare in relation to global health and environmental threats: lessons from the COVID-19 crisis. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(3):e004111.

Stengel S, Roth C, Breckner A, et al. Resilience of the primary health care system – German primary care practitioners’ perspectives during the early COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23:203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01786-9.

Adu PA, Stallwood L, Adebola SO, Abah T, Okpani AI. The direct and indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child health services in Africa: a scoping review. Global Health Res Policy. 2022;7(1):1–4.

Segal M, Giuffrida P, Possanza L, Bucciferro D. The critical role of health information technology in the safe integration of behavioral health and primary care to improve patient care. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2022;49(2):221–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-021-09774-0. (Epub 2021 Oct 19. PMID: 34668115; PMCID: PMC8525847).

Gallardo-Rincón H, Gascon JL, Martínez-Juárez LA, Montoya A, Saucedo-Martínez R, Rosales RM, Tapia-Conyer R. MIDO COVID: A digital public health strategy designed to tackle chronic disease and the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Plos One. 2022;17(11):e0277014.

Shah SS, Safa A, Johal K, et al. A prospective observational real world feasibility study assessing the role of app-based remote patient monitoring in reducing primary care clinician workload during the COVID pandemic. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22:248. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01594-7.

Lu M, Liao X. Access to care through telehealth among US Medicare beneficiaries in the wake of the COVID-pandemic. Front Public Health. 2022;10:946944.

Reges O, Feldhamer I, Wolff Sagy Y, Lavie G. Factors associated with using telemedicine in the primary care clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(20):13207.

Neves AL, Li E, Gupta PP, Fontana G, Darzi A. Virtual primary care in high-income countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: Policy responses and lessons for the future. Eur J Gen Pract. 2021;27(1):241–7.

Fadul N, Regan N, Kaddoura L, Swindells S. A midwestern academic HIV clinic operation during the COVID-19 pandemic: implementation strategy and preliminary outcomes. J International Assoc Provid AIDS Care (JIAPAC). 2021;2(20):23259582211041424.

Gray C, Ambady L, Chao S PharmD, Smith W MPH, Yoon J. Virtual Management of Chronic Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights From Primary Care Providers and Clinical Pharmacists. Mil Med. 2023;188(7-8):e2615-e2620. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usac277.

Hincapié MA, Gallego JC, Gempeler A, Piñeros JA, Nasner D, Escobar MF. Implementation and usefulness of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. J Prim Care Commun Health. 2020;11:2150132720980612.

Calvo-Paniagua J, Díaz-Arribas MJ, Valera-Calero JA, et al. A tele-health primary care rehabilitation program improves self-perceived exertion in COVID-19 survivors experiencing Post-COVID fatigue and dyspnea: A quasi-experimental study. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0271802. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271802. (Published 2022 Aug 4).

Chen K, Davoodi NM, Strauss DH, Li M, Jiménez FN, Guthrie KM, et al. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41(11):2282–95.

Murphy M, Scott LJ, Salisbury C, Turner A, Scott A, Denholm R, Lewis R, Iyer G, Macleod J, Horwood J. Implementation of remote consulting in UK primary care following the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods longitudinal study. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71(704):e166-77.

Maria AR, Serra H, Heleno B. Teleconsultations and their implications for health care: a qualitative study on patients’ and physicians’ perceptions. Int J Med Inform. 2022;1(162):104751.

Liddy C, Singh J, Mitchell R, Guglani S, Keely E. How one eConsult service is addressing emerging COVID-19 questions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(3):601–4.

Schow DC, Thomson A, Trusty WT, Buchi-Fotre L. Use of a research as intervention approach to explore telebehavioral health services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Southeastern Idaho. J Prim Care Commun Health. 2022;13:21501319211073000.

Bruns BE, Lorenzo-Castro SA, Hale GM. Controlling blood pressure during a pandemic: The impact of telepharmacy for primary care patients. J Pharm Pract. 2022;27:08971900221136629.

Pradhan NA, Samnani AA, Abbas K, Rizvi N. Resilience of primary healthcare system across low-and middle-income countries during COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2023;21(1):98.

Esfahani P, Mosadeghrad AM, Akbarisari A. The success of strategic planning in health care organizations of Iran. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2018;31(6):563–74.

Otu A, Okuzu O, Ebenso B, Effa E, Nihalani N, Olayinka A, Yaya S. Introduction of mobile health tools to support COVID-19 training and surveillance in Ogun State Nigeria. Front Sustain Cities. 2021;5(3):638278.

Ndayishimiye C, Lopes H, Middleton J. A systematic scoping review of digital health technologies during COVID-19: a new normal in primary health care delivery. Health Technol. 2023;13(2):273–84.

Ghiasipour M, Mosadeghrad AM, Arab M, Jaafaripooyan E. Leadership challenges in health care organizations: The case of Iranian hospitals. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2017;31(1):560–7.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Arshad Altaf for his invaluable comments on the earlier drafts of this work.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LE, MA, MZ and AMM participated in the design of the study. LE, AMM, MA, MZ, PI, FE, MA and SHA undertook the literature review process. All authors drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Tehran University of Medical Science (Approval ID: IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1401.0979).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mosadeghrad, A.M., Afshari, M., Isfahani, P. et al. Strategies to strengthen the resilience of primary health care in the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 841 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11278-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11278-4